Five Black Sports Legends You Probably Didn’t Learn About in School

Black excellence in sports is often celebrated, but the deeper legacy—the one born on segregated fields, dusty tracks, and in gymnasiums closed to the public—is frequently overlooked. Before the mainstream spotlight reached athletes like Jackie Robinson or Wilma Rudolph, there was an entire generation of Black pioneers who built the foundation. These were men and women who dominated their arenas despite racism, exclusion, and erasure. Their stories weren’t in your school textbooks, but they should have been.

This is their story.

1) Ora Washington: The Tennis Phenom Who Dominated Before Wimbledon Knew Her Name

Source: Temple University Libraries, Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection, John W. Mosley Photograph Collection Long before Venus and Serena Williams graced center court and changed the face of tennis, there was Ora Washington—a pioneering athlete whose excellence laid the foundation for generations to come. In the 1920s and 1930s, Washington emerged as a dominant force in tennis, winning eight national singles titles and twelve doubles titles through the American Tennis Association (ATA), the oldest African American sports organization in the United States. The ATA was formed in response to the exclusion of Black players from the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association, a reflection of the deeply entrenched segregation that defined American sports during that era.

Washington’s reign on the court was nothing short of legendary. Her powerful forehand, strategic acumen, and unrelenting competitiveness made her virtually unbeatable in ATA competition. She was not only a champion but a symbol of Black excellence in the face of widespread discrimination. Yet, despite her dominance, she was barred from competing against the top white players of the day, including tennis legend Helen Wills Moody, due to the racial barriers of the time. Washington reportedly challenged Moody to a match—an invitation that was never accepted, depriving the world of what could have been one of the sport’s most historic showdowns.

But tennis was only one chapter in Ora Washington’s remarkable athletic story. She also excelled in basketball, playing center for the powerhouse Philadelphia Tribune Girls, one of the most successful all-Black women's basketball teams of the 1930s. With Washington leading the charge, the Tribune Girls claimed numerous championships and were often described as unbeatable. She was a fierce competitor on the court, known for her speed, agility, and leadership. Her prowess made her one of the earliest examples of a two-sport professional athlete—long before the term became popularized.

Despite her undeniable talent and trailblazing legacy, Ora Washington’s name was largely omitted from mainstream sports history for decades. Her story is emblematic of how segregation and racism not only restricted opportunities for Black athletes but also erased their contributions from the broader cultural narrative. Today, efforts to recover and honor her legacy are part of a larger movement to acknowledge the overlooked heroes of Black athletic history—those who shattered ceilings, even when the world refused to recognize their greatness.

Ora Washington wasn’t just ahead of her time—she helped define it. She was a champion in every sense of the word: resilient, brilliant, and unyielding in her pursuit of excellence, even in a world that refused to see her as equal.

2) Major Taylor: The Fastest Man on Two Wheels

Source: National Museum of American HistoryMarshall “Major” Taylor was a cycling prodigy and one of the first international Black sports superstars—rising to prominence in the 1890s, when bicycle racing was among the most popular and grueling sports in America. Born in Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1878, Taylor earned his nickname “Major” from wearing a military-style uniform while working in a bike shop as a teenager. It was there that his extraordinary talent caught the attention of cycling promoters, and by his late teens, he was shattering racial and athletic expectations on the racetrack.

Taylor wasn’t just fast—he was phenomenal. He set multiple world records in sprint cycling events and, in 1899, became the world champion in the one-mile race, making him only the second Black athlete to win a world championship in any sport, after Canadian boxer George Dixon. He dominated the track with explosive speed, tactical brilliance, and unmatched endurance. Yet his victories came at a steep cost.

Despite his sportsmanship and skill, Taylor faced relentless racism at home. White competitors and race organizers often refused to allow him to compete. When he was permitted to race, he endured unspeakable hostility. Fellow cyclists would attempt to box him in, shove him off the track, or even physically assault him during and after races. Spectators hurled slurs. Some race officials turned a blind eye, while others tacitly endorsed the abuse. He was frequently forced to change in barns or alleys because he wasn’t allowed in locker rooms, and many venues outright banned him simply for being Black.

Frustrated but undeterred, Taylor took his talents abroad—racing in Europe and Australia, where he was celebrated for his athleticism and treated with far more dignity. In France, Germany, and other countries, thousands flocked to see him race, and he was often received as a respected competitor. While racism was not absent overseas, Taylor found a level of recognition and fairness that eluded him in his home country. His international success underscored a painful truth: Black excellence was often more accepted abroad than on American soil.

Taylor’s career was not only a testament to his physical prowess but also to his moral conviction. A devout Christian, he refused to race on Sundays and consistently carried himself with grace, refusing to respond to violence with violence. His autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World, detailed his journey and the toll racism took on his health and spirit.

Marshall “Major” Taylor was a pioneer, a champion, and a symbol of resilience. His story is a powerful reminder of the barriers Black athletes have had to overcome—not just in competition, but in the battle for basic human dignity. Though history tried to relegate him to the sidelines, Taylor’s legacy now rides strong as a trailblazer who opened the door for generations of Black athletes to come.

3) Fritz Pollard: NFL Pioneer and Playmaker

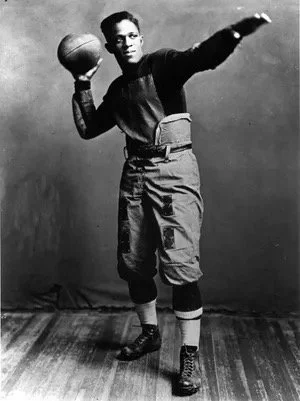

Source: Brown UniversityFritz Pollard wasn’t just one of the earliest Black players in the National Football League—he was a revolutionary figure who broke barriers both on the field and the sidelines. Born in 1894 in Chicago, Illinois, Pollard excelled academically and athletically from a young age. He went on to attend Brown University, where he became the first Black player to compete in the prestigious Rose Bowl in 1916. At a time when college football was largely segregated, Pollard stood out not only for his speed and agility as a running back but also for his leadership and intellect.

After college, Pollard joined the professional ranks, signing with the Akron Pros. In 1920, during the NFL’s inaugural season (then known as the American Professional Football Association), Pollard helped lead Akron to the league’s first championship. His exceptional play on the field was matched by his strategic mind—qualities that earned him the role of co-head coach in 1921, making him the first Black head coach in NFL history. At a time when Black leadership in sports was virtually unheard of, Pollard’s coaching appointment was a groundbreaking moment in American athletics.

But his time in the league was short-lived. As the NFL grew in popularity during the 1920s, so too did the influence of racism and segregation. By 1933, NFL owners had adopted an unspoken but widely enforced “gentleman’s agreement” that barred Black players from joining the league—a de facto ban that would remain in place until 1946. Fritz Pollard, one of the league’s brightest early stars, found himself shut out not because of his talent, but because of the color of his skin.

Rather than step away from the game he loved, Pollard fought back. He formed and coached several all-Black teams—including the Chicago Black Hawks and the Harlem Brown Bombers—providing opportunities for Black athletes to showcase their talents when mainstream avenues were closed to them. Beyond coaching, Pollard became a vocal advocate for integration in sports, writing articles, speaking at public events, and challenging the hypocrisy of American athletic institutions that preached fairness while practicing exclusion.

Pollard was not just an athlete—he was a businessman, a race relations pioneer, and a symbol of Black resilience. He opened a talent agency, launched a newspaper, and used his platform to promote racial justice long after his playing days ended. Until his death in 1986 at the age of 92, Fritz Pollard continued to call for an NFL that truly reflected the nation’s diversity and values.

His legacy lives on through the Fritz Pollard Alliance, a modern organization named in his honor that advocates for diversity in NFL coaching, front-office, and scouting positions. Fritz Pollard was more than a trailblazer—he was a movement. His story reminds us that history isn’t just shaped by rules on the field, but by those who dare to challenge the ones off of it.

4) Tidye Pickett and Louise Stokes: Barriers on the Olympic Track

Source: University of Notre DameIn 1932, amid the harsh realities of Jim Crow America, Tidye Pickett and Louise Stokes made history as the first Black women selected to represent the United States in the Olympic Games. Hailing from Illinois and Massachusetts respectively, both young sprinters had shattered records in track meets across the country. Their inclusion on the U.S. team for the Los Angeles Olympics marked a monumental breakthrough—not just for Black athletes, but for Black women, who faced compounded discrimination based on both race and gender.

Yet their journey to the Olympics was anything but triumphant. From the moment they qualified, Pickett and Stokes were subjected to racism from white teammates, coaches, and officials. On the road to Los Angeles, they were forced to travel and lodge separately from their white peers. Once at the Games, the discrimination became even more blatant. Despite earning their spots in the 4x100 meter relay, both women were benched in favor of slower white runners—an exclusion widely believed to be motivated by race rather than performance. They had trained tirelessly, overcome barriers, and earned their place—but were denied the opportunity to compete on the world stage.

Four years later, at the 1936 Berlin Olympics—a Games already steeped in racial politics under Nazi rule—Tidye Pickett finally became the first African American woman to compete in the Olympics, running in the 80-meter hurdles. Though she was injured during a semifinal heat and unable to finish, her presence on the track in Berlin was a powerful statement. She stood not only as a symbol of athletic excellence but as living defiance against both American segregation and Hitler’s Aryan ideology.

Louise Stokes, though never given her moment on the Olympic track, remained a pioneer in her own right. She went on to become a beloved figure in her Massachusetts community, working with youth and advocating for sports as a means of empowerment.

The courage and dignity shown by Pickett and Stokes in the face of racism helped lay the foundation for generations of Black women Olympians who followed—icons like Wilma Rudolph, who overcame polio to win three gold medals in 1960; Florence Griffith-Joyner, whose speed and style redefined the sport in the 1980s; Allyson Felix, one of the most decorated track athletes in Olympic history; and Sha’Carri Richardson, whose bold presence and brilliance on the track reflect the legacy of those who blazed the trail before her.

Tidye Pickett and Louise Stokes may not have come home with medals in 1932, but they carried something even more powerful: the weight of a movement and the promise of what was to come. Their story is a testament to how breaking barriers isn’t always about crossing finish lines—it’s about showing up, standing firm, and daring to run in a world that tells you not to.

5) Isaac Murphy: Horse Racing Royalty

Source: J.H. Fenton (1885) on Wikimedia Commons, via Library of CongressDid you know that 15 of the first 28 Kentucky Derby winners were Black jockeys? In the years following the Civil War, Black riders dominated American horse racing—a sport they had helped to build through generations of enslaved grooms, trainers, and stable hands who developed deep expertise in handling thoroughbreds. Among these early stars, one name stood above the rest: Isaac Burns Murphy.

Born in 1861 in Kentucky, just as the Civil War began, Murphy rose to become one of the greatest jockeys in horse racing history. Known for his extraordinary strategy, composure, and almost telepathic bond with horses, Murphy won the Kentucky Derby three times—in 1884, 1890, and 1891—and achieved an astounding career win rate of nearly 44%, a record that remains one of the highest ever in the sport. He was admired not only for his skill, but also for his integrity: he refused to throw races, even when pressured by powerful owners or gamblers.

Murphy’s brilliance, however, came at a time of growing racial backlash. As Jim Crow laws spread and segregation became more entrenched in American life, the success of Black jockeys began to provoke resentment from white competitors and race organizers. Through intimidation, discriminatory licensing practices, and outright bans, Black riders were gradually pushed out of the sport they once ruled. By the early 20th century, Black jockeys had virtually disappeared from major races—not because of a lack of talent, but because of the systemic racism that shut them out.

Isaac Burns Murphy died in 1896 at the age of 35, and for decades, his legacy faded from public memory. Like so many Black pioneers, his accomplishments were largely omitted from mainstream historical narratives. It wasn’t until the late 20th century that historians began to reclaim his story, unearthing the records and retelling the remarkable achievements of this once-forgotten champion. Today, Murphy is recognized as a trailblazer—a Hall of Fame athlete whose name belongs alongside the greatest in any sport.

His story is more than just one of personal triumph. It is a reflection of how Black excellence has often been erased, and how reclaiming that history helps us understand the full picture of American sports. The next time the horses thunder down the track at Churchill Downs, remember: the roots of that legacy are Black, brilliant, and too powerful to forget.

Why These Stories Matter

The mainstream narratives of athletic achievement too often begin at integration—as if Black excellence only mattered once it could be measured in desegregated box scores or televised milestones. But the truth is: excellence didn’t wait for permission.

Long before the color line was crossed, Black athletes were already making history—on dusty fields, in segregated gyms, and under the weight of a system built to erase them. They didn’t just play sports; they challenged the status quo. They ran, jumped, rode, boxed, and strategized their way into greatness—often denied recognition, yet never defeated in spirit. In doing so, they redefined the very meaning of resilience, power, and Black potential in an America that tried to keep them invisible.

These pioneers weren’t anomalies—they were architects of a legacy that still shapes the game today. Their stories are not sidebars or afterthoughts. Their names deserve more than footnotes in history books. They deserve headlines. They deserve the spotlight.

At Black Sports Health, we’re committed to telling these stories—the full story of Black athletic excellence, past and present. From early legends like Isaac Burns Murphy and Ora Washington to today’s icons breaking barriers in real time, we’re here to honor the legacy and continue the conversation.

Want to learn more?

Stay tuned and follow us for powerful history, athlete features, and sports health insights rooted in culture and truth.

📲 Instagram: @blacksportshealth

📲 TikTok: @blacksportshealth

Because Black sports history is American history. And we’re just getting started.